- Home

- Gigi Amateau

Macadoo of the Maury River

Macadoo of the Maury River Read online

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE A Great Belgian

CHAPTER TWO The Battle

CHAPTER THREE You Are My Home

CHAPTER FOUR One Last Wish

CHAPTER FIVE Nothing of Value

CHAPTER SIX To the Kill Sale

CHAPTER SEVEN John Macadoo

CHAPTER EIGHT A New Tomorrow

CHAPTER NINE Arrival and Departure

CHAPTER TEN Cedarmont

CHAPTER ELEVEN In Izzy’s Service

CHAPTER TWELVE Poppa and Old Job

CHAPTER THIRTEEN Molly

CHAPTER FOURTEEN Watch Closely

CHAPTER FIFTEEN Our Splendid Mountain

CHAPTER SIXTEEN Can You See the Wind?

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN Christmas

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN Christmas Secrets

CHAPTER NINETEEN A Boy’s Grief

CHAPTER TWENTY Into the Bald

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE A Family at Cedarmont, Again

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO The Far End of the Field

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE Mira Stella

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR The Virginia Auction

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE The Maury River Stables

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX Who Am I Now?

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN Hop Aboard

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT Another New Job

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE The Smallest Child, Claire

CHAPTER THIRTY Here for You, Always

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE The Old App

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO The Watch

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE A Gentle Peace

In his darkest hour, a friend once asked, “What if they sell me?”

Such fear tangled up in that question: What if I am not needed, no longer useful? What if I am not wanted, no longer loved? What if I am forgotten?

The quiver in his voice pierced my heart, plunged through flesh, blood, and bone and into memory. “What if they sell me?” he asked.

Here is how I answered.

I was born at a place for breeding horses but not for keeping horses in Alberta far from the Maury River where I call home now.

I remember as a yearling I surveyed my pasture and the jagged gray mountains beyond the fence.

“If you dare, just try to beat me!” I called. I raced past every mare grazing in the summer grasses, and I dashed by every foal standing in the rocky field. The colts and the fillies gave chase, but I crested the hill first, many lengths ahead of them all.

When the fastest filly caught up, she head-butted me, slamming into my shoulder with all her strength, but she was not strong enough. I stood on the tip of a great boulder jutting out from the ground, and, like the stone beneath me, I would not be moved — not by the wind and not by the filly.

I nickered for her to come at me again. “One more try,” I urged her.

She spun around, pawed at the ground, and made a big show of snorting. She backed up and charged. This time, I dodged her battery, and the filly fell down into the tall grass.

“I’m king of the hill!” I proclaimed. “Bow down to serve me.”

A cabbage white butterfly of silken cream, unconcerned with my victory over the filly, lit across the white clover blossoms. She circled my cannon and flitted down my hoof. She fanned her wings, came softly to rest on the grass, and tickled my foot with her legs. Butterfly kisses.

The filly — a draft like me — was strong and powerful. The butterfly looked delicate and fragile.

“I can play gently, butterfly. You’re safe with me,” I reassured her.

The butterfly darted around my ear and then disappeared away down the hill. Because I was enchanted with the cabbage white, I didn’t see or hear anything else happening until I heard the mares sounding an alarm.

Our caretaker, Janey, had left a new farmhand in charge for the day. He had let the stallion into our field by mistake, then walked away. The stallion shouldn’t have been let into the pasture. Mixing up stallions and colts could endanger the mares and the weanlings.

When I heard the mares shouting, I forgot my butterfly game of wings and flight. I needed a place to hide. I turned to bolt, but before I or the filly could run, a long, dark shadow overtook us.

Behind me a voice bellowed, “Little Horse, why don’t you tell me who is king of the hill?”

Stepping out of my blind spot, a blond stallion appeared. A white blaze ran the length of his face, and white socks painted all four legs. His coat glistened. Every rippled muscle from his neck to his hocks pulsed as if it were its own living thing. My sire!

My father, I thought, must be among the greatest of Belgians.

He blocked our path. “Step aside,” he ordered the filly.

She took off for the far end of the pasture.

The stallion rammed his shoulder hard into mine. “Walk with me, son. I only visit this farm in the summer to breed, but today I was let into pasture earlier than usual — a mistake. But, while I’m here, let me tell you something.

I moved in closer to my sire. One day, I thought, I will be just like him. He stared off toward the horizon. He didn’t graze the clover or notice the butterflies. I nibbled dandelion leaves and waited to hear the reason for his visit. What did I need to know?

“By now, the yearlings have usually already gone. Still I’m not supposed to be in your field until tomorrow. So we haven’t much time before they remove me.” The great Belgian snorted loud like thunder and nodded toward the mares below us. “Which is your dam?”

I whinnied toward Mamere, who stood apart from the others.

“Ah, Tina. We are old friends. Your mother has lived here for many years. She’s the leader when I’m gone,” he said. “She is lovely.”

I sunk deep into my hooves and stretched my head high, as if I were the tallest lodgepole pine of the forest, with roots to anchor me to the earth and limbs to scale the clouds. I reached up, up, up but fell short of the stallion’s withers; still I found the courage to correct him. “Mamere’s the leader all of the time,” I said. “This is her herd.”

“Do you know who you’re speaking with, young colt?”

“Yes, you’re my sire. Mamere told me I will grow big like you. She says I will be a very great Belgian someday,” I said.

“And, little king, what do you think it means to be great?” he asked me.

I puffed my chest far, far out. “It means everyone looks up to me most of all, that every filly and colt and mare serves me.” I stomped my foot. “That I get to eat first and do whatever I want.”

He said, “It’s true; you were bred a fine Belgian. And I have seen you playing with your siblings and cousins today, and you are fast and strong, but being king is not a game.”

The great stallion set his gaze upon Mamere’s herd. He lifted his head into the wind, and I did so, too. He trotted back and forth across the hilltop, all the while watching the mares and yearlings. I tried to keep up but tired quickly.

“What did you want to tell me?” I couldn’t wait any longer.

The stallion stopped suddenly and snorted. He held me there under his fiery stare, and then he said, “You need to learn your place, young one, and your place is not here. When I’m here, this is my herd. Not yours. Not Tina’s.”

I scraped the grass, and then a dandelion blossom, white and hairy, tickled my nose so deep that I sneezed it away into a hundred flying pieces.

The Belgian sniffed the wind, then whinnied toward the mares. They hardly noticed him prancing along the hilltop.

“Have they forgotten me, too?” he said to himself. “These mares have forgotten me just like the world has forgotten the draft horse.”

“Forgotten? How could anyone forget about us?” I asked.

“You don’t even know who you are, li

ttle horse. Who we are. We are descended from the Great Horse of Flanders. We are warhorses, nation builders, movers of mountain and forest. We were. We’re coming to the end, I fear.” Then, without a nicker or a whinny, and before I could ask him anything more, the stallion galloped away. I could not stay with him even for a stride. I returned, alone, to my high spot on the hill hoping the white butterfly would return.

To save Mamere I would do the same tomorrow, I thought, but tangles filled my belly, knotting me up so that I could not graze but could only wonder: What did the stallion mean about all of us being forgotten and how could I find my purpose?

All afternoon that same day, the stallion watched Mamere from where he hid behind the run-in. Janey still hadn’t returned so no one had removed him from our field. Mamere turned fierce when he came too near. He bit and charged at the mares and tried to corral the fillies, but Mamere protected all of us from him. She led the mares and yearlings to the bilberry patch growing through the south fence to keep them safe from the stallion.

In response, he kicked. He bucked. He smelled the sky and bared his teeth, then bit at the air around him, and then he charged toward the herd. “I am the king of this field,” he proclaimed.

With a sudden, piercing scream, Mamere turned and made him stop. He craned his neck to sniff Mamere’s flank.

The other mares lifted their heads from the lush grass and stood alert. The fillies squeezed closer in behind their own dams. The very trees around us seemed to freeze, for even the always-constant wind had fled our field.

Then the stillness in the pasture gave way to a battle. The stallion launched a strike to take over the field, but Mamere would not give in. She was going to fight him. As Mamere and the stallion fought, a dust cloud swallowed them up.

Janey was nowhere to help us. The mares and fillies and colts didn’t dare help her. No one did.

So I raced into the battle and ran to my dam’s side. A fire like I had never felt before burned in me. I couldn’t stop myself; I reared, ready to fight the stallion to my death or his. Already, he looked lathered and winded from Mamere’s attack, so I struck his haunch, which was as high as I could reach.

He spun around to find that it was I — only a silly colt — who had drawn his blood. From a slender, open gash, blood trickled down his hindquarters. I brandished my front hooves and moved to strike again, but suddenly Mamere folded me into her.

The stallion stared at us. “Your dam was almost right. Centuries ago you would have been a great horse, but you will be forgotten, too — a Belgian draft made for humanity but without any purpose and with no guarantee of love. The world has almost forgotten us. All of us. If you don’t find your purpose, son, you’ll end up like me.”

“I will never be like you. And I will forget you tomorrow.”

“No, you will remember me, and now you will remember what I’ve said.” Then the stallion nibbled at me as if he were savoring a tasty morsel of red clover. When his searching lips found the soft fine place he was seeking, he plucked off the very end-tip of my ear in an instant — before Mamere or I even knew what he had done.

A pain, radiant and sharp, filled the newly vacant space, yet I stood beside Mamere and preened my chest, as if it had never happened. A rivulet of blood ran down from the missing place onto my cheek. The stallion spit my ear bit onto the ground.

Then he walked, alone, to the corner of the pasture. The mares and foals gathered near Mamere, and I began to tremble.

“My darling?” Mamere whispered.

I leaned in close to her.

“You will make a very great horse. And I will remember what you did this day.” Mamere blew onto my ear, then lay down in the grass to rest.

Later that afternoon, Janey returned to the barn and removed the stallion and our field returned to peace.

Safe, again, with no need to stand guard, I dozed in the shade of the giant white spruce shuddering in the wind. Mamere grazed beside me. Though my ear throbbed, I dreamed of how I had saved her.

I stretched awake and whickered across the grass. The mares and their foals were spread across the pasture.

Even when our caretaker, Janey, entered the field with our grain, Mamere stayed by my side.

“I heard trouble found your colt yesterday. Let me get a look at him,” Janey said. She flung her hands in my dam’s face to drive Mamere away. “Go on, Tina!”

Mamere flattened her ears at Janey, and the woman only laughed. “Missy, I know you can’t be pinning your pretty ears at me. All I do is dote on you. You’ve been my best mare for fifteen years.” Before Janey could examine me, she saw all the cuts and swollen places and hoof prints on my mother — hoof prints from the stallion.

“What happened to you? Let me see, girl.”

My dam turn the swollen side of her face toward Janey. The sight of her best mare covered with bruises and her left eye swollen shut made Janey pull back.

“Oh, boy. Why did I let anyone else handle the stallion?”

Then she noticed my now-cleft ear and reached out to touch it. I twitched her hand away.

“Decided to take on big daddy, did you? Handsome, but not the smartest cookie in the jar, I think.” She rubbed away dried blood from my cheek and neck.

“You picked a lousy time to fight a stallion, I’ll tell you that. Now you’re deformed! You’ve lost the tip of your ear. We’ll just hope that won’t matter. You’re still a nearly perfect colt,” Janey said, then she ran her fingers through my forelock. “All right, stop pouting; I admire your courage, little one. I’d keep you for my own if I could.”

Janey tickled my mouth, and Mamere nudged my head up.

“Besides,” Janey said. “Some very fine people have gone missing a bit of their ear, you know. Van Gogh comes first to mind.” Janey patted my neck. “My favorite artist, Van Gogh. We could name you after one of his paintings. Hmmm . . . so many to choose from, aren’t there? We could call you Marcelle, after The Baby Marcelle? No, no, that won’t do. You’re a Belgian; you won’t be a baby forever. I suppose you might like to be called Basket of Apples, or, would you rather eat a basket of apples?”

She smiled at me and scratched my neck. “I’ve got it now. Cypress! Van Gogh loved to paint the cypress. If I could, I would name you Cypress. I will miss you, sweet one.” Janey sighed.

Where is Janey going now? I wondered.

Janey kissed my head and started toward the barn. I spurred a long breath across the ground. The sugary dew at dawn made morning grazing ever so sweet, but my nagging dreams of the stallion had a stronger hold on me than breakfast.

“Mamere,” I asked, “why did my father let me win?”

She tugged at the fescue but kept quiet. I nipped at her shoulder until she answered me.

“Because the legacy of our breed lives on in colts like you. Even the stallion, with all his strength and courage, grieves that we have lost our place in the world, and still, even he has hope that we will be restored. Your sire could not fight his own son to the death. You, and all the yearlings, are his living hope. He could not kill you.”

“I don’t want to be the stallion’s son. He’s mean and selfish and no one likes him.”

Mamere nuzzled me. “My darling, you are my son, too. You acted quickly and with fierce courage when our herd was under attack.”

“He told me that all the yearlings are usually gone when he comes here. Where do we go?”

My dam grazed without answering me. She would not even look up or whicker or nuzzle. I had never seen Mamere so withdrawn from me or the herd. The sun breached the hilltop, silhouetting the fillies and colts gathered there.

“He said I need to find my place — Isn’t my place here?” I stomped the ground and demanded that she respond.

But she only said, “Child, run along. The day is getting away from you. Enjoy the sunshine and run in the wind with your friends. We will talk tonight.”

Since I had fought the stallion, the other foals wouldn’t race me. The colts only prete

nded to contest the highest spot on the rock, and the fillies hardly put up a good fight.

When I swished my tail to bother away a horsefly, a small cabbage white butterfly — the same one from before — flew off, too. Right away I saw that her right wing, which yesterday looked a perfect match with the left, now had its pure-white tip torn and ripped.

She should have been resting her broken wing beneath the shade of a tree. Yet, she busily spiraled around me, then touched down lightly on my withers. I worried the sunshine might scorch her, so I turned to make her some shade. I stood as still as I could while she rested. She fluttered up and settled near my cleft ear, and then I remembered the stallion, again.

All day instead of racing colts and fillies, I stayed with the butterfly. At last, when the great horned owl awoke to take his hunting post in the old dead pine, the ivory butterfly vanished into the night. And I raced down the hill to Mamere.

“Mamere!” I called out as I galloped down to her. “Mamere! Today I met a butterfly with a broken wing, just like my ear. And I helped her!”

She nickered me quiet while she inspected my ear.

“Tomorrow I will help her again!” I shouted. “I’ll spend the entire summer finding nectar and shade and places for her to rest.”

“Helping others is what makes you great. That’s your purpose. Believe in that for all your life.”

Then Mamere spoke somberly. “Come near to me; stand close, like you did when you were a much smaller colt. One day you will grow even taller than I am, my sweetest.” And her voice grew quiet.

She bent down to nuzzle me, and her breath smelled of sweet molasses. “Let me tell you a story I have told too many times. Yes, I know where you are going. Tomorrow, you will leave me. Not just for a day, or a week, but to start a new life in a new place.

“Darling, you were bred to help every living creature. Service is the way of the draft. Your life’s work is to serve and to please, to heal when you can, and to bring a gentle peace to those in need — whomever and wherever they are.”

“Like the hurt butterfly?”

“Yes, that’s right. All Belgians were born for this reason,” Mamere said.

Macadoo of the Maury River

Macadoo of the Maury River Dante of the Maury River

Dante of the Maury River Come August, Come Freedom

Come August, Come Freedom Chancey of the Maury River

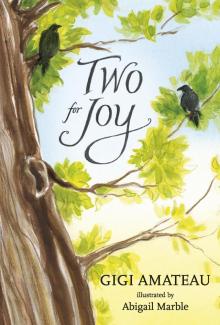

Chancey of the Maury River Two for Joy

Two for Joy