- Home

- Gigi Amateau

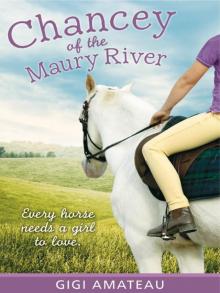

Chancey of the Maury River

Chancey of the Maury River Read online

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE Prophecy

CHAPTER TWO Horse for Sale

CHAPTER THREE Reprieve

CHAPTER FOUR My New Home

CHAPTER FIVE My True Companion

CHAPTER SIX The Maury River Band

CHAPTER SEVEN A Mother’s Intercession

CHAPTER EIGHT A Fine First Horse

CHAPTER NINE Beyond Saddle Mountain

CHAPTER TEN Under Saddle

CHAPTER ELEVEN A Fancy Pony

CHAPTER TWELVE She Fell Up, Then Down

CHAPTER THIRTEEN Waiting Out the Storm

CHAPTER FOURTEEN Ode to Joy

CHAPTER FIFTEEN A Bombproof Pony

CHAPTER SIXTEEN My Training Begins

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN Canis Familiaris

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN Equus Asinus

CHAPTER NINETEEN Three Times Weekly

CHAPTER TWENTY A Child Like Me

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE Under Claire’s Instruction

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO The Ridgemore Hunt

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE Yah, Boy!

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR Fulfillment

Tonight, the moon was high and full; it cast a light so pure that all fell quiet and still under its watch. Even I felt its pull.

A fire star raced across the winter sky, causing quite a stir among us. The younger ones were afraid and ran to their mothers. I no longer feared the wild streak, as I had in my youth. Instead I dropped my head and gave thanks for a long and good life lived here by the Maury River and in these blue mountains. I gave thanks, too, for the friends who have stood beside me through these many years.

When I was still a colt, I once saw a fire star burning with such a fury that it scared me greatly. I thought it was coming straight for me. I raced to the corner of our field and, unable to find my dam, became filled with an anxiety so invasive that I began to breathe too fast and thus found no breath at all. But I was in no danger. My dam came to me. She wrapped me in her neck, and I was no longer afraid.

My dam explained that when a horse of great beauty or wisdom enters the world, a star chosen especially for that horse lights across the night sky, announcing the new arrival. Dam told me that we should not fear the fire stars; instead we should drop our heads and say a word of thanks for life’s many blessings. Dam allowed that occasionally the blaze is so bright and so near that it is frightening, as most things are if you don’t understand them. She encouraged me then, and on many such occasions, to seek understanding in all things. I have remembered this for my whole life and only rarely do I feel afraid. When I do, I try to remember Dam’s words, then find my breath, and examine that which frightens me.

After that night, I sought out fire stars in the sky. Most nights, I did not see any at all. Sometimes, in the late summer, it seemed that the night held so many that I quickly lost track and would fall asleep watching them, still standing in the field.

“Was there a fire star on the night I was born?” I often asked Dam.

Each time I asked, she would pull me in to her and recount the story of my birth.

“Oh, yes, Chancey. On your night, a star raced across the sky with such brilliance that all present knew you would grow beautiful, wise, and great. Something very special is planned for you.”

For years, I believed her; I held tight to Dam’s faith that I would become a great horse.

My owner, too, had grand hopes of me. She had planned that I would become a champion, and a beautiful one at that. She bred my dam, a fancy snowflake Appaloosa, to an identical stallion, certain that I would turn out the same, black as night with white snowflakes blanketing my hind. Dam’s markings were so vibrant that at her own birth she was given the name Starry Night, not for the sky under which she was born but for the way in which she was adorned with a midnight quilt of icy diamonds.

Yet I am very nearly the inverse of my stunning parents; I was born without pigment. Black stripes do cut through the middle of all four of my hooves, the one physical characteristic I possess which proves to all that I am a true Appaloosa. And so, despite my lack of pigmentation, I believed my dam. I believed greatness awaited me.

Here now, in my old age, I comprehend what I could not before comprehend. I understand now that mothers are apt to wish on stars; every mother prays to heaven on behalf of her child. Sometimes, it seems that a mother’s prayers for her child will never be answered at all. Yet is it not possible that one day, when that child is very, very old, he might see that his mother’s prayers have been perfectly, beautifully answered all along?

That I had never been sold away was a blessing of immeasurable comfort. I had lived my entire life as a school horse here in this valley. Friends had come and gone, yet my comforts remained constant: the Blue Ridge Mountains, the Allegheny Mountains, and the Maury River all surrounding me. These mountains, all blue to me, were home.

I was grateful, too, that I had lived a life of service under the care of a decent-enough owner. I had seen cruel hands on others, and I was deeply aware of my position. Though throughout much of my life I longed for something more — the greatness, perhaps, that my dam foresaw — I was content to have been treated fairly. My fortune changed, however, when my owner’s fortune changed overnight.

The day before had ended the same as most days. We were led to our rooms, given our grain, and the barn was closed up for the evening. But the next morning, no one came to feed us. By the time the sun had moved high into the sky, we all were hungry and panicked. We kicked our doors until finally some of the students arrived to feed us and turn us out.

Monique, the proprietor of the stable and my owner, did not show. That was the first day since my birth that I had not seen her. Though I did not love Monique, I depended on her.

The students who came in her place spoke in hushed tones and whispered of the terrible and sudden death of Monique’s husband. These whispers also spoke of a debt incurred by the dead man, a debt so enormous that it might force Monique out of her fine brick home and off of several hundred mountainous acres. In the second it took her husband to release his final breath, Monique had been stripped of her status as a wealthy and privileged landowner. There was no recourse left for Monique but to sell everything, including us horses, so that she could return to her native land, a country so far away that she planned never to return to the blue mountains.

Monique priced all of us reasonably. Many of my fieldmates sold quickly, purchased by current or former students who held a sentimental attachment to their favorite school horses. I recognized these buyers and had taught some of them myself, in their youth and mine. Yet I alone remained — the sole horse for sale.

I suppose, if you have never before been any girl’s or boy’s favorite horse, no heart longs for you.

With good reason, I was apprehensive that I would be sold at auction in Lynchville. Lynchville held no promising future for a horse like me. In fact, Lynchville offered no future at all, only a guarantee that my remaining days would likely be spent in suffering. Kill sales, like the one in Lynchville, employ unspeakably cruel techniques. Among horses, the code of kill buyers is widely understood — they’ll do whatever it takes to load a frightened horse who resists his fate en route to slaughter. I have heard that breaking all four legs or cutting out eyes is commonplace. I would as soon have chosen to fend for myself in the blue mountains and taken my chances against bear and coyote than to have loaded willingly for Lynchville.

Monique warned of the distinct possibility of Lynchville as she appealed to our neighbors to extend some small charity to her by taking me in temporarily. The stables around Rockbridge County had known me since I was a colt. This fact alone should have made it easier for me to find a home, for who would so easily

turn away a longtime neighbor now in need? As we set out, I was hopeful that my breeding and years of experience were assets enough to offset my obvious liabilities.

Rockbridge County has never seen a shortage of young, healthy horses. When a horse half my years, and of impeccable health, could easily have been purchased at an attractive price, there seemed no economic benefit to using me as a school horse. Though athleticism and endurance run through my Appaloosa blood, though agility and strength flow into my Appaloosa muscles, though courage and loyalty live deep in my Appaloosa bones, my aches and difficulties defy all this.

My prior career as a school horse had been long and diversified. In my youth, I introduced dozens of girls to the artistry of dressage. I carried many a young man through the mechanics of learning to jump. School horses are rarely asked to jump much higher than three feet, for by the time our pupils grow strong and skilled enough to master an intricate course of twelve three-foot jumps, they are well on their way to competing on finer horses than I. Still, for twenty or so faithful years, I had schooled without complaint, nearly every day and often for many hours.

Monique tried desperately to convince each of the barns we visited that I would make a versatile and valuable addition to their stable, capable of teaching hunt seat, dressage, basic equitation, and jumping. We made the rounds to places I had shown before, all managed by trainers I had seen on and off throughout my life in the blue mountains. I concealed my flaws as best I could. We made no less than four trips to local barns, all of which held plenty of school horses and were not in need of another.

For some time now, my powerful hind had hurt on days when it was too hot or too cold. It hurt me to jump, as a school horse must. This pain was not all that hindered me. My other ailment, I did not like to think about, and for years, had tried to deny. Our neighbors had all heard Monique’s complaints about my refusal to jump. They were disinclined, each of them, to believe that I could be of value to their riding schools.

I felt certain that Monique would have accepted any offer made. Yet her pleading on my behalf resulted not in a purchase or even an offer. I feared that the Lynchville auction was my destiny. I resigned myself to never again seeing my blue mountains or feeling the Maury River swirl around my feet or hearing its roar after a heavy rainfall.

Long after Monique’s house, barn, and land had sold to new owners, I remained alone, standing in my field. Though the new owners were horse people themselves, their primary interest was in the breeding of fine Thoroughbreds for the track. They brought no horses with them, as they intended to start a breeding farm only after certain improvements had been made to the buildings and land. As I was not only gelded but also of the wrong breed, not to mention my age, lack of pigmentation, and chronic conditions, the new owners declined Monique’s offer of me as a gift. They did, however, agree to let me stay on if Monique would make arrangements for my care until a proper home could be found. I do not know what those arrangements might have entailed as no evidence of them ever presented itself to me.

I had been cared for well enough throughout my life. Like most school horses, I relied on structure and routine. Until this time, I had come to expect fresh hay and a rather healthy scoop of grain twice daily — once to be given just after sunrise and once again in the evening. Now I waited and waited for someone to come with hay, grain, and water, but no one arrived.

By nightfall of my first solitary day, I had eaten all of my grain and much of my hay, and drunk a good bit of water. I remained convinced that the morning sun would bring a caretaker with more rations. Morning came and brought with it a dense fog, but no caretaker. I was not alarmed, but assumed that once the fog lifted, provisions would arrive for me. The fog hung so thick that I could not see even the copper vane atop the barn. For the entire day, the mountains were but shadowy layers of themselves, for there was no sun to light up the trees or disperse the clouds.

I could see nothing of Saddle Mountain, which naturally rises and falls in precisely the shape of an English saddle. I strained to see the highest peak, what would be the saddle’s cantle, but it was lost to the sky. Even the lower peak, the pommel, was hostage to the grave clouds which had descended upon me. The unseasonable mix of moist pockets of heat and cold sealed in the fog until nearly nightfall. I finished the hay left in the ring and passed the time by searching for one spot in the field that would give me some glimpse at all of Saddle Mountain. For the entire day, I could not see beyond my own feet.

Long after the fog lifted, I waited there at the gate, sure that Monique herself would show up, or an attendant on her behalf. Only once did I see any activity near the barn. I made a dancing fuss of my displeasure at being kept alone and without suitable food for so long. No one responded to my pleas for help. The activity was not intended for me; workmen had come to survey the barn and surrounding property for the new owners, who had not yet arrived. There was nothing left in the hay ring — nor a fleck of grain in my bucket — and I had resorted to licking the muddy water in the tub at the back of my field. Had I foreseen that I would be standing alone in the back of the field for more than one season, even more than one day, naturally I would have conserved my first day’s rations.

During this time of uncertainty, I was consoled by the evidence around me that I was still home. Seeing my blue mountains and just knowing, from the sloping tree line, where I could find the Maury River provided my only solace. Though in my solitude I deeply felt the absence of my former life of comfort and routine, I realized that I remained, after all, in the very field in which I was born.

Upon taking full measure of this fact, that everything I had ever known was as near me as ever, I found it unnecessary to stand a moment longer pacing at the gate, filled with indignation and concern about my future. The new day did, indeed, feel new! With the fog chased off, my thoughts were as clear to me as the blue mountains now on display for as far as I could see in the golden light of morning. I must test my resourcefulness on this land I knew so well, or suffer greatly while waiting for a phantom custodian to arrive.

Fortunately, the winter had been milder than average. I judged by the duration of sunlight during the day that winter had surpassed its halfway point. During Monique’s prosperity, the field had held twenty horses comfortably, so I knew I could survive for some time on grass. I also knew that should I awaken to find no grass, I could subsist for a short while on the lichen that covered the protruding boulders in my field. I had seen deer graze in this way, on lichen and moss. With no snowfall, except for a light dusting that had occurred nearer the darkest time of winter, my field was, if not lush, at least sporadically green.

While the absence of a snow cover on the ground gave me grass to graze, it left me without a ready source of water. Because of my extensive experience as a trail mount, access to the Maury River was as familiar as my own skin. On a trail ride of eight or ten miles, I would often lead riders across the Maury River. At certain points, the Maury runs narrow like a brook — narrow enough that, on a good day, I could jump clear across its banks. At least, in my youth I could. I knew every sycamore tree along its banks and each stark-white river birch, too.

I was even more familiar with the fence line than the river. I knew its vulnerabilities and where it was in need of repair. The front fence line, the side best seen from the road, was made of handsomely maintained white-painted wood. The back fence line consisted of cedar posts strung with barbed wire. A cedar-post fence, if properly constructed, makes smart use of wood planks secured diagonally across the barbed wire between every few vertical cedar posts. The purpose of these diagonal posts is to reinforce the barbed wire, keeping it taut and stable down the line.

Though not ideal for the containment of horses, the barbed-wire fence proved a blessing in my quest for water. I knew exactly where the fence line was weak. I trotted to the place in the fence where the cedar reinforcements had long ago rotted away and used this to my advantage, for I was determined to forge a path to the Maury. It took some

work, but I managed to widen a hole enough to give me mostly clear access to the unfenced portion of the farm, which in turn opened the Maury River to me. In pushing open the fence, I sustained numerous cuts and gashes, but none were life-threatening. I grazed on new grass and drank freely from the water. It was in this way that I kept myself fed and hydrated during Monique’s absence.

Though I missed the regimen of two good meals served daily, and the warmth of my private room in the barn, I also felt satisfied. I survived, in fact quite well. Near the river, I discovered a lush patch of sarsaparilla, growing just for me it seemed. Though, if truth be told, I prefer the taste of peppermint to sarsaparilla, I found that the pain in my hocks and hips eased considerably when I cabbaged this plant routinely from the forest. A dense thicket of old, proud cedar trees in the middle of my field provided suitable cover, protecting me well from rain and even from wind. And though the winter sunlight cannot be considered harsh, there were times I found that the sun proved too strong for my eyes. The respite of the cedar stand gave me needed relief. I even found warmth there after sunset. I have always been partial to cedar trees, perhaps because of their abundance and familiarity to me. During this time, they proved essential.

As soon as I had secured my basic needs of food, fresh water, and very adequate shelter, my thoughts turned to my owner, Monique. Alone with the blue mountains and the Maury River, I reflected on all that had passed between Monique and myself since my birth. I had known her my entire life. Since I could remember, it was her voice that called me in from the field and her hand that filled my grain box. To my knowledge, I had received acceptable medical treatment, when needed, for both prevention and cure. I had remained active and working. My most basic needs were never neglected. I now pondered as I had never done before the questions of why I had so long remained in her care and why we had grown into such adversaries over the course of my life.

In the many years that had passed between us, horses had been born; horses had been put down for illness or injury. Ponies had been bought for pleasure, then sold for not bringing enough pleasure or not quite measuring up. I knew that I had been spared sale because some part of Monique could never part with her last remaining connection to Starry Night, the stunning snowflake Appaloosa who was my dam.

Macadoo of the Maury River

Macadoo of the Maury River Dante of the Maury River

Dante of the Maury River Come August, Come Freedom

Come August, Come Freedom Chancey of the Maury River

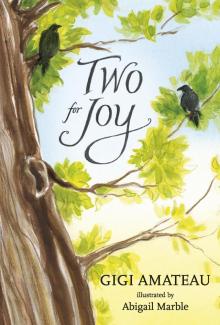

Chancey of the Maury River Two for Joy

Two for Joy