- Home

- Gigi Amateau

Chancey of the Maury River Page 2

Chancey of the Maury River Read online

Page 2

Monique was so entirely devoted to my dam that she wanted to replicate her in me. Her dejection at my albinism never waned from the moment she discovered me nursing from Dam in the field. She realized right away that she had miscalculated. Not only was my appeareance abhorrent, but to Monique and others like her, my albinism was evidence that I was a weaker, flawed specimen.

As constant was her love for Dam, Monique was as uniformly constant in her indifference toward me. Because of Dam’s great attachment to me and her sense of purpose in raising me, Monique tolerated me, I believe. After my dam’s death, which came sooner than it should have, Monique and I did not replace her with each other, for too much resentment had built up between us. We avoided each other, at best.

As I grazed in solitary confinement, with no horses or people to distract me from my thoughts, I realized I had never before considered the possibility that my dam’s death had hardened me, too, as much as it had hardened Monique. Standing alone in my field, the very field where Dam and I were torn apart, I found that what I longed for most was the belonging that I had with Dam and the mares of my field when I was a colt — a belonging that I had not found since. Yet it seemed a prayer that I petitioned too late.

Perhaps I would have been content to stay alone in the field until the new owners completed their work and dispensed with me. Or perhaps I would have gambled all and fled to the blue mountains to start over on my own. The thought of innumerable seasons of fallen leaves whirling under me as I cantered higher and higher up the mountainside was luring me to set out for the forest. Granted, though I had only run through the mountains under saddle, I had always been reliable and resourceful on the trail. The terrain of the blue mountains can be challenging, but I had never lost my footing, even down the narrowest, rockiest cliffs. It would have been a different life to be sure, but I had begun to consider the idea of forging a feral, solitary existence in the blue mountains.

The doorway I had made in the fence line stood open and waiting for me to decide. Though I had spent plenty of time trying desperately to remove my halter, for it cut deeply into my face and I wished it to be off completely, I now began to take heart that the halter had, indeed, been left fastened to me. Halters serve but one purpose — to catch and lead a horse. I had first wondered for what purpose Monique had abandoned me; now I wondered for what purpose she had left me haltered.

One afternoon, as I was again evaluating the option of fleeing to the mountains by way of my hard-earned passage through the barbed wire, Monique herself appeared at the gate and called me to her. I trotted to the gate, demonstrating my eagerness to join with her. Curious, and surprised to see her, I greeted her warmly with a light touch to her chest. I detected a new softness to her, perhaps there all along, perhaps made with grief from the loss of her husband. In days prior, I surely would have objected to my conditions and made known to her my displeasure at the halter having been left so tightly bound to my face. I gave Monique no fight as she hooked the lead rope to my halter. I thought of Dam and her devotion to the woman standing before me and decided that I could start over with Monique, and hoped that Monique could, too.

Monique did not speak to me, so I made the first overture. I nickered long and low into her ear. I blew across her neck with the intent to acknowledge everything we had been through together and also my willingness to begin anew. Monique paused. She sighed deeply and looked around the field, the same field that had once held Dam, the mares, and me when I was a colt. I lifted my head to see more clearly. Was Monique remembering Dam, as was I? The blue mountains encircled the two of us, urging our reconciliation, it seemed to me. I blew on Monique again. I pushed my head into her neck, not hard as if I wanted grain this very instant, but softly, to welcome her home to our field.

I believe now, and will always believe, that for an instant, Monique considered forgiving me as I had just, finally, forgiven her. But the relief that mutual forgiveness brings was not to be. She took me by the halter and pulled my cheek to her face.

“Since when have you nuzzled anybody? Much less me?” She then pushed my head away.

I made no further attempt to reconcile. Monique brushed her hand across her eyes and led me out of the field.

She had arrived with a trailer in tow; I dropped my head and consented to load without a struggle. Unsure whether I was going to Lynchville or someplace I had not considered, I looked toward the blue mountains for what I prayed would not be the last time.

Despite my failure to fulfill her expectations, our lifetime together had entreated Monique to make an act of kindness on my behalf. She had arranged for one last visit to a local barn in an effort to plead my case. The Maury River Stables, owned by Mrs. Isbell Maiden, was the fifth facility we had visited in our mission to find a proper home for me. I knew as we turned into the drive that this place would soon become my home. While Monique approached Mrs. Maiden, I remained in the trailer, watching the two women from the window.

I had always observed Monique to be taller than the average woman; she had no need of a mounting block.

She always held herself with exceptionally straight posture, which she urged all of her students to emulate. She could not have been credited with exceptional posture on that day. Bent over in defeat and having lost an entire life, Monique made a desperate picture of grief. Wearing dark glasses, and with her head wrapped in a scarf that tied under her chin, she spoke quickly and curtly of the gravity of my situation. The scarf and dark glasses were surely added for dramatic effect, but that is solely one horse’s opinion.

Unhesitatingly, Mrs. Maiden agreed to house me, albeit temporarily, with the understanding that Monique would work toward finding a suitable, permanent home elsewhere. I committed myself to expressing only gratitude toward Mrs. Maiden. Even this temporary improvement in my situation, one that allowed me to stay in the blue mountains, was beyond my greatest hope.

Monique didn’t seem wholly satisfied with the offer. Rather, she acted quite put upon when Mrs. Maiden suggested that compensation be granted for my food and care, even if only for a portion of it. I overheard Mrs. Maiden tell Monique that she herself had been in the position before of having to rebuild her entire life after a great loss.

“That’s why I’m helping you,” she impressed upon Monique. “I believe in women helping women.”

I maintain that her husband’s death and the resulting divestiture of her entire stable and riding school had exhausted Monique entirely of all civility.

“You can drop the women helping women bit,” she snarled at Mrs. Maiden. “All of your horses are leftovers like him. Why do you think I brought him here? I’ve never known you to turn away any horse for any reason.”

Upon hearing this, I wondered why we had not started out with the Maury River Stables to begin with, but as we were safely arrived and all seemed to be working out in my favor, I did not make a commotion. I did badly want out of the trailer. Still, I did not kick or snort. I listened to the two women negotiating the terms of my acceptance to the Maury River Stables.

If Mrs. Maiden felt intimidated by Monique, as many people had over the years, she did not show it. Mrs. Maiden reaffirmed her position, “That’s true; I love all horses. But I can barely keep the barn running month to month. Anything you could do to offset my costs for keeping Chancey while you get straightened out would help.”

Monique acquiesced; she wanted to be done with me. She agreed to send funds when she could, but I believe we all understood that funds would not be forthcoming.

I unloaded agreeably when Mrs. Maiden asked for me. Though I was thankful that Monique’s last compassionate act brought me to the Maury River Stables, I had hoped for a warmer good-bye or even some small acknowledgment of our many years together. But my owner had no departing words for me. Mrs. Maiden led me toward the barn as Monique started the truck. I turned back to watch her leave, and stood square as she drove off. Mrs. Maiden waited for Monique’s truck to disappear before she inspected me thoroughly.

I was first placed in a round pen, where I now understand all new horses are kept for an introductory period of sorts. The day was pleasant enough, though the sun was too bright in my eyes, as I could not escape its glare at all in the round pen. My eyes burned in the full gaze of the sun. By contrast, in my old field I could easily find shelter under my cedar stand, a shadow cast near a hay ring, or even shade thrown off by a tractor to protect my fair eyes and pink skin.

Mrs. Maiden called to a young girl for help. The girl came quickly but kept her eyes cast to the ground as she walked. I judged her to be ten years of age and later was proven correct in that judgment. She was tiny then, and with her dark hair cut short above her ears, looked very much at home in worn overalls and dirty boots. One of her overall flaps was undone and hanging loose from her shoulder. The child didn’t seem aware or concerned. I thought I detected a smile when she saw me, but perhaps it was the sun that caused her face to appear brighter.

Mrs. Maiden explained to her, “Claire, this is Chancey. He’ll be staying here at the Maury River Stables with us for a while, until he finds a home.”

Then Mrs. Maiden instructed me, “Claire is one of my very favorite students, Chancey. I want you to be especially kind to Claire; she’s having a bit of a tough time right now.”

Claire reached her hand out to me. I nickered at her, hoping she would come closer. She did not come to me, but she did look up to Mrs. Maiden and say simply, “He’s b-b-beautiful.”

Not one to perpetuate a lie, as I would later learn, Mrs. Maiden said, “Well, he’s not beautiful right now. He’s a mess. You could make him beautiful, Claire.”

Claire did not respond in any way, except to look at Mrs. Maiden and squint her eyes.

Three young girls, obviously just arriving for their riding lesson, strode over to us arm in arm. Claire stepped out of their way. To me they appeared nearly indistinguishable from one another, turned out just exactly as every little barn girl I had ever taught, wearing crisp white shirts, brand-new riding pants, and leather paddock boots. Each of the three wore her hair in a long ponytail. Though I suppose I shall never tire of giggling girls in jodhpurs, I rather preferred the likes of Claire already.

“Hi, Mrs. Maiden,” the girls sang in unison. Though the girls looked to be Claire’s age, they did not greet Claire, except for the smallest girl, who waved. Claire waved back and smiled.

“Good morning, ladies,” Mrs. Maiden boomed. “Go get tacked up quickly. I’ll join you in the ring shortly. Stu is up there now with the beginners.”

The girls skipped off to the barn with their arms still linked. I continued watching Claire; she showed no interest in joining the trio now preparing to ride.

Claire dropped her head to the ground and quietly said to herself. “Ch-Ch-Chancey’s already a gorgeous pony. He d-d-doesn’t need me to make him beautiful.”

Mrs. Maiden turned her attention from the girls back to Claire. “Oh, but he does, Claire. He does need you. Chancey’s been through so much. So much that we could never possibly begin to know, and it’s all bottled up inside of him. Look at him. His coat is matted, and his mane is knotted with burrs thicker than my fist.” Mrs. Maiden tugged on my forelock and lifted my mane to show Claire its horrendous condition. Then she pointed to my cheek.

“The poor horse’s face is cut so badly it’s as if someone slashed him with a knife, though I suspect he somehow got tangled up in barbed wire. That’s exactly why you should never fence horses in barbed wire — ever! And look at his legs, all swollen and cut, too. Claire, when was the last time you saw a horse this thin? Even with his winter coat, he’s nothing but bones. Run and get a bucket of grain; he can eat while we’re cleaning him up,” she instructed Claire.

Claire returned in an instant. I waited but long enough for Claire to step away from the bucket before I began to consume the grain. How I had missed the taste and texture of sweet feed! I had not forgotten it, but I had beaten my palate into disciplined acceptance of whatever I could forage from the ground. I devoured the grain with such speed that it must have been shocking for Claire to watch.

“Oh, my gosh. He’s so hungry, Mrs. Maiden. I’ll help him,” Claire told her. I stopped licking the residue from the bucket and lifted my head to the girl. She scratched my ear.

“This horse needs a friend like you, someone he can really count on. Chancey needs a girl who will love him for who he is and accept everything he has to offer — then the world will see the horse you see.”

Claire stepped closer to me and tentatively reached both arms around my neck. She held me ever so lightly; I felt her eyes close against me.

“Claire,” Mrs. Maiden said. “Why don’t you ride with the girls today? It’s been a while since you’ve ridden with them.”

For barely a second, there was excitement in Claire’s voice. “Ride Chancey?”

Mrs. Maiden shook her head. “Not yet. You know he’s not ready, don’t you?”

Claire nodded, her eyes welling up with tears. Mrs. Maiden squatted down to eye level with the girl. My muscles, the ones with any feeling left, ached deeply. My heart, which had fallen into a very deep sleep over the winter, began to stretch itself awake. I leaned more toward Claire.

Mrs. Maiden put her arms around Claire and pulled her little body in close. Claire wiped her eyes and nose with her hand.

“I want you to listen to me. I know you are hurting right now,” Mrs. Maiden said. “Divorce is never easy. I’ve been there myself and even though it was the right thing, it hurt my two boys badly.”

“You have ch-children?” Claire asked.

“Yes, one is grown up now. He lives in Roanoke,” Mrs. Maiden explained.

“What about the uh-uh, the other one?” Claire asked.

Mrs. Maiden did not answer right away. Claire did not ask the question again but began picking the mud and rocks out of my feet. Over the years, I have observed that most little girls protest vehemently about cleaning a horse’s feet when they are as unsightly as mine were on that day. Claire did the task as if it were only casual work to busy the hands. Not once did she say an unkind word. She had finished with my feet and brushed my entire right side before Mrs. Maiden answered her question.

“My younger boy died when he was thirteen.”

Claire placed her hand on Mrs. Maiden’s shoulder. “Oh, that’s sad,” she said.

“Yes, I will always be sad,” Mrs. Maiden replied. Then Mrs. Maiden perked up. “You see Daisy over there?”

Claire nodded.

“Daisy was my son’s first horse. Boy, were those two a pair; they were inseparable. Here’s what I’m trying to tell you, Claire. There comes a day when you have to let go of the pain and let love come back to you. That might just be why Chancey came here, to bring love back to you.” She kissed the girl on top of her head and turned back to the business of restoring me.

“Claire, bring me a fly mask from the tack room,” Mrs. Maiden said.

“Why?” the girl asked. “The f-flies aren’t, aren’t out yet.”

Mrs. Maiden motioned for Claire to come nearer. “Come here; I’ll show you why.”

Claire, eager to know why I ought to have to wear a fly mask in March, ran to Mrs. Maiden’s side.

“Look at Chancey’s eyes,” Mrs. Maiden instructed. “What color are they?”

“B-blue,” answered Claire, not yet making the connection.

“Yes, they’re blue. They’re blue, just exactly like yours are blue.” It gave me immediate pleasure to know that the girl and I shared something already. Mrs. Maiden continued the lesson. “Now, look at the skin on Chancey’s muzzle. What color is

it?”

“P-pink!” Claire was enjoying this lesson very much, I could tell.

“Yes, his skin is pink. And his coat is all white, isn’t it? These things tell us something about Chancey; he’s an albino, or a partial albino, anyway. You’ll hear some people say there is no such thing as a true albino horse. Others will say Chancey can’t be albino because his eyes are blue, not pink. But none of that matters to us. His eyes are blue, his skin is pink, and that tells us that the sun is harder on him than all of the other horses we know. A fly mask will keep the sun from damaging his eyes any further.”

“D-does he have to wear the f-fly mask all the time?” Claire wanted to know.

“While he’s with us he will, even on cloudy days, except at night. Run into the tack room now and find him one.” Mrs. Maiden dispatched Claire, again, to the tack room. Claire ran off and came straight back with a dusty fly mask, torn at the clasp. She rose to the tip of her toes to adjust the fly mask over my poll. My eyes relaxed. I felt Claire’s two hands fasten the fly mask under my neck. She leaned her face into my shoulder and inhaled.

“He smells good,” Claire said, while Mrs. Maiden examined me for more cuts and scrapes.

“He smells like a horse, Claire.”

Mrs. Maiden didn’t look up from behind me. I still felt embarrassed by the condition of my feet, all four cracked and overgrown. Only one shoe remained intact, as I had thrown the others in my effort to widen the hole in Monique’s fence.

“I love how horses smell,” Claire told her with such pride that I forgot my distress at Mrs. Maiden spending so much time examining every part of me. Claire breathed me in again. Unable to help myself, I inhaled Claire’s hair, too. She smelled like a girl.

Macadoo of the Maury River

Macadoo of the Maury River Dante of the Maury River

Dante of the Maury River Come August, Come Freedom

Come August, Come Freedom Chancey of the Maury River

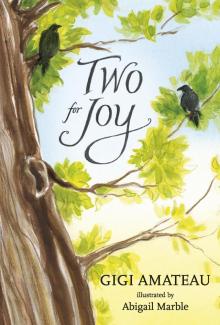

Chancey of the Maury River Two for Joy

Two for Joy