- Home

- Gigi Amateau

Macadoo of the Maury River Page 4

Macadoo of the Maury River Read online

Page 4

In the first months of my life at Cedarmont, Izzy and I would remain in the field for hours, alone and together, surrounded by beauty enough to draw our grief out into the open mountain air, where mourning doves lamented with us. Walking together in my paddock made us grow stronger together.

“Walk on, Mac. Walk on,” Izzy would say. He knew when it was right to lead me down the shady side of our field toward the happier-sounding birds — cardinals, phoebes, bluebirds, and mockers — all reminding Izzy and me how good it felt to stand in the sunshine.

Sometimes, we would leave the field. “Walk on,” he’d say, and cluck for me to follow.

The boy loved to explore the meadow. He marveled at the changing nature of our mountain home. He showed me every little thing he recognized — delicate white Queen Anne’s lace, flowering blackberry vines, and raptors circling overhead.

On summer nights, when the sun and the flies were sleeping, I grazed the pasture, while Izzy gazed at the stars. Each night, my boy named the stars and their families.

“I like knowing each star’s name and its home in the sky,” he would say, and point out stars with names like Bear and Great Dog.

And once, I saw stars combining into the shape of a great horse. Izzy saw it, too. He rested his head on my withers. “Do you know Pegasus, Mac?” he wanted to know.

I nickered.

“Pegasus is a horse — a horse with wings!”

Izzy pointed up. “There! See?”

In our summer of horses and bears in the sky, Poppa tried to coax Izzy into riding — not me, for I was still a yearling. I weighed nearly one thousand pounds already, but a baby’s bones are too soft for work. Besides, just walking with Izzy, being near him, learning his voice, and letting him lead me was job enough for a colt.

But Izzy was not interested in riding lessons anyway. The earth around him fascinated him more than the thought of riding instruction.

I saw what his poppa could not see. Izzy never dreamed of winning ribbons or collecting trophies. Learning about all the creatures that lived on our splendid mountain was the calling of Izzy’s heart and mind.

Mamere had told me: “You are a Belgian, born to serve, to heal, and to bring a gentle peace.”

To be in Izzy’s service brought both of us peace. To be always within the sound of Izzy’s voice was my joy. Coming to him whenever he called. Moving with him out of the sun, into the shade, and back into the sun again. Standing next to him for as long as he cared to explore the world around him, for however long he remained helped him as well as me.

He and I were the same — motherless, now, and new to this place. Even in the absence of his words or tears, I knew the loss of his mother was the source of his suffering. His grief and mine bound us to each other.

Our carefree days of summer ended when Izzy started school. One morning after I had been at Cedarmont long enough for the moist, hot air of summer to turn dry and cool, long enough that I had grown some but not enough to reach my head over the fence where the maple branch hung nearly within reach, Poppa called me to him.

He told me, “You and Izzy have brought happiness back to Cedarmont. Watching him with you this past month, Macadoo, has given me something, too.” He turned his face to the sky. “You’ve been through a lot. So have I. So has Izzy.”

Poppa kissed me on my cheek.

“Look over there at the Allegheny Mountains”— then he swept his hand in a wide half circle to the east —“and here in our yard, you see the Blue Ridge Mountains. How lucky are we, eh? Tucked away on a little farm in the Shenandoah Valley, where every day we wake up to these mountains.”

Poppa led me through a different gate to a different pasture. “Here you are, boy,” he said. “No more quarantine for you. This is your new field. You’re ready to become part of our little herd now. You are home.”

I looked for colts and fillies to play King of the Field, but none rushed to the fence. I looked for other Belgians to play Chase and Find, but I saw no Belgians. Then something moved under the trees.

Poppa pointed to the back fence line. “See that mule up there? You’ll be in here with old Job.”

At the top of the field, I saw the back half of a horselike body, swishing its tailing. He kept grazing, and by the looks of him, he mostly liked to graze, not run.

Poppa pushed me forward. “Go on, Mac. Run! Play!”

Before, I had only imagined running through the distant Alberta mountains, as the reigning Draft King of Alberta, but now, at Cedarmont Farm, as far as I could see were soft mountains and grassy fields all around. And no one but an old mule to play with me.

After Poppa turned me out and left me in the new paddock, I ran straight to the back-field cedars to greet Job. I sidled up and pretended to nibble the grass. Though the trees were letting go of their leaves and the air was turning cooler, the pasture remained full with clover and fescue. I moved a bit closer to Job and flicked my tail right in time with his. He pinned his ears and hawed. “Go away!”

The mule showed me his backside and picked at red clover. “If I go away, will you come find me?”

“What?” Job snapped his tail. He lifted his back leg in midair and held it ready to strike.

I stepped aside. “We played this game in Alberta. I run away someplace in the field. You run after me.” I pranced around Job and shook out my mane. “Ready?”

With a mouthful of clover, he hawed again. “Go away, now!”

OK I thought, so I galloped away, past the three oaks, all the way to the run-in. I hid out there and waited for Job. Inside, scraps of old hay were strewn about the floor, and brilliant spiderwebs spanned the ceiling. I flushed barn swallows, finches, and sparrows.

After a long while, I peered around the wall to spy on Job. He stood at the bottom of the paddock, pulling at overgrown grass from a dip in the ground.

This mule knows how to play! I thought. He wants me come find him!

I charged straight for Job, then I slowed to an easy run, and reared beside him. Job flattened his ears and let out a piercing screech.

Job kicked out with his back feet, so I did, too. “Again!” I urged him. “Ready?”

The mule kicked, again, this time from his side, but he missed me. “See those four ducks?” he said. “Go play with them!”

I turned and charged toward the four white ducks visiting from the neighboring pond. “Hello, ducks! Macadoo, King of the Drafts, is coming your way!”

So, while I raced the birds and the breeze, Job watched over the field. “You, go play with your birds,” Job would often say. “I’ll stand guard.” When I needed rest, he guarded me. And once, after I had spent a tiring morning flushing swallows from the run-in, leading ducks around the paddock, and avoiding the geese under the trees, Job showed his compassion as the true king of our field — a different sort of king than my father.

“Go to the north corner, near where I have been standing all morning,” he told me. “There are a few blackberries still, and I have kept your birds away.”

We grazed the bushes together, and Job let me be King of the Ducks. “Strictly ceremonial title,” he said. “This is still my field.”

I asked my mule one day, “Have you ever walked through those mountains?”

He lifted his head as if remembering would take him there. “Many times” was all he said. He pushed his muzzle into me and nudged me toward the freshest hay.

The last of the monarch butterflies lit upon my poll and fiddled with my ear. I remembered my father’s message to me, but I still didn’t understand it.

“Job, do you think Izzy and Poppa will ever forget us?” I asked him.

“Do you know how long I’ve lived here?” He answered me before I could guess. “Twenty years. I am part of Cedarmont like that mountain is part of Cedarmont.”

I grazed beside him for a long time, thinking about what he said and what my father had said, too.

“I only met my father once,” I blurted out.

“Well, that

makes you fortunate. Most of us never know our sires. My mother, though, was beautiful. A bay quarter horse, fifteen hands. I loved her dearly.”

“My father told me that we used to help people build cities. We used to clear mountains and help men win wars. He told me we are near the end of our usefulness. That we will be forgotten.”

Job walked to a new grazing spot. He showed me a patch of clover blossoms. “There are enough cities. Mountains should keep their trees, and peace is better than war. No, your father was mistaken. Our work today is more important than ever in our history.”

“Can you tell me more about our important work, Job? I want to know everything,” I said.

“In time, son. Your most important work today is to grow strong and stay gentle. The rest, you will learn in time.”

I nuzzled the mule and whickered low. And I wished that my father had known a mule like Job.

During the fall at Cedarmont, we grazed in the field during the warmth of day and came inside for evening grain. Job had introduced me to the third of our group, a gigantic mule, even bigger than I, named Molly. Her stall was across the aisle from Job’s and mine, but she rarely spoke to either of us. Not in the barn. Not from her field, where she grazed by herself.

“Molly.” Job had tried to get her attention that first night in the barn. “The colt is one of us now.”

The mule slowly finished eating, then turned toward the front of her stall and spoke to me. “Every horse should be so lucky to live at a place like ours — at least, for a short time. Tell me, do you love Cedarmont?” she asked.

“I love Job. I love Poppa and the splendid mountains. And I love Izzy most of all.”

“Then, I should say you love Cedarmont,” Molly rumbled. “Every day, we must be grateful — much more so than Poppa or even Izzy — for Job and I and especially you, know how quickly our luck could change.” Then she turned away and went back to licking her grain bucket.

She was so bossy and tall, as tall as Mamere, and I was a little glad that I had Job in my field and not her.

Through the wide hole in our shared wall, Job told me, “Her mother was a Rocky Mountain mare, and her father . . . her father was an American mammoth jack! That’s why she’s so big.”

“Well, I’ll grow bigger than her!” I kicked the wall hard. “I’m a Belgian!”

Job turned his backside to me and leaned against the wall to scratch himself. “I meant, she’s big for a mule, son.”

He set a mouthful of grain between our two stalls. I gobbled it up. He put his face close, and I puffed a breath over him.

“Macadoo,” Job said. “I have seen the horse in Molly, and it is grand.” He nickered.

“What’s funny?” I asked.

“And I see the mule in you! Consider that a compliment.” Job scratched himself again. “Not to worry, Macadoo. You and Molly’ll become friends, just like you and Izzy and you and I. Molly knows everything about this place. I’ve learned new plants, new trees, and when Molly and I go up into the mountains together, I feel young again. You could learn something from her, too, you know.”

I turned away from Job. What could I learn from a cranky mule that I hadn’t already learned from Mamere?

“You might be interested in this, Job said. “Molly knows how to unlatch her stall door. That could come in handy, don’t you think?”

I ignored Job and sniffed at my door.

“Now, tell me about your dam, Macadoo. Tell me what she’s like.”

“Even though we are apart now, I know she is still with me. Mamere was a broodmare. She saved me from the kill sale, and I saved her, too. My dam is beautiful and strong. You would like her, I think.”

I looked across the aisle. Molly had her whole entire head buried in her grain bucket, licking for the very last morsel. What could I possibly learn from her?

I might have been content to run with ducks and butterflies through our paddock, but Molly and Poppa and Izzy started playing in the riding ring next to us. Job and I watched them there between the house and the field.

Poppa had urged Izzy to learn to ride and convinced him to try by telling him that the view of the trees and birds and the whole wide world appeared different from the saddle than from the ground. “Izzy, you are a curious boy. I’m surprised you’re not interested in seeing the world around you in a new way.”

“How so, Poppa?”

“Come see for yourself! I promise Molly and I will keep you safe.”

So, I watched Molly carry Izzy on her back and step carefully over poles set down on the ground in the shape of a wheel. After a few weeks of practice, and once Izzy loosened his grip on the reins and relaxed in the saddle, they took to the poles again, this time at the trot. Poppa showed Izzy how to let Molly bend in spirals and turn in serpentines. The mule kept one ear on Poppa and one on Izzy.

I paced up and down the fence line, calling to them. Even when I whinnied, Molly would not look away from her work. Izzy looked every time. “Hi, Mac! Watch closely, boy. Pretty soon, it’ll be you and me riding.”

I longed to run and spiral, too. When would it ever be time for me to carry Izzy? Trotting back and forth, I wore a hard path in the grass. Poppa, Molly, and Izzy paid no attention. I whinnied with an extra-long haw that sounded like Job, but only Job answered me. “Go on, chase away those sparrows! Go!”

Mostly, Job and the sparrows were my delight, until Poppa taught Izzy how to jump. Then, not even the song of a wren or meadowlark could deter me from watching the ring. I went back to my worn path and begged, “Let me try! Let me jump with you!”

I stomped the ground. I rammed the fence. Poppa kept me out. Even after they had finished and gone back into the barn, I waited by the ring for a long time, imagining that I was carrying Izzy over poles and fences.

Job came to get me, and, this time, he did not order me to go away. The mule swatted me with his tail — a tail so long it dragged on the ground and collected burrs and hay as he walked through the field.

“Come with me to the new grass at the top of our field,” he said. “I’ve saved it for us, just for today.”

I wanted to jump, so I ignored Job the way everyone else had ignored me. But Job was king of our field, and kings usually get what they want.

“Let’s race!” Job challenged me, and he tore away up the hill.

I had no time to say I don’t feel like running; no time to say I feel more like jumping. Job raced away without me. His hay belly swayed side to side as he moved from a trot to a canter. Job, the mule, was beating me to the top of our hill.

I knew what I had to do. I cantered by the three oaks, stirred up the ducks, galloped past the run-in, and beat him. I was still the fastest of the field!

“I’m Macadoo, King of the Ducks!” I said as I ran by him.

“Where are you going?” Job asked.

“I’m going to jump!”

And I did. I ran faster than I had ever run before, so fast that the white oaks blurred to my right as I passed them. When I reached the gate, I did just as I had seen Molly do. I sprang up off my hind legs, and looking straight out at the paper birch beyond the barn, I lifted myself up.

Can I reach the mountains? Will I hover in the air? I flung my legs straight up and out.

I soared right into the hot metal that burned my belly. I scrambled to untangle myself from the gate, now bent and swinging by its bottom hinge. I stood up and shook myself out.

Job reached me first. Huffing, and out of breath, he said, “Go away. To the run-in. Now.”

“But — I.”

“Now.”

My guardian gave me an order, so I galloped off and hid there, peeking from behind the shelter. At the mangled gate, Job stood, hanging his head, as if he had tried, but failed, to clear it. He swished his tail pitifully in unison with gate’s creaky wobble. Job even gave his lip a quiver.

Poppa came out from the barn limping to the scene, without his cane, and laughing out loud. I left my hiding place. I could tell he was

n’t angry about the damaged fence.

Poppa nuzzled Job. “Well, you old fool. A tad jealous of Molly, are you? Or has Macadoo got you feeling young again, the way Izzy has me? I should have guessed as much.” He patted the mule on the neck; then Poppa rubbed his chin. “You sure you caused all this trouble?” He looked over at me; I ate some clover.

“Mac, you’re still a baby,” Poppa said. “But, you’re getting bigger. From the size of you, I’d guess you must be nearly two now. I don’t suppose a slow walk in the mountains would do you any harm. Tomorrow, we’ll teach you to pony beside Job. I believe both of you boys are feeling a bit frisky. And, who wouldn’t be, surrounded by this beauty?”

My heart raced at the thought of walking in the mountains. Job pushed his head into Poppa’s hand and got a scratch behind his ear.

“Soon we’ll go exploring,” Poppa promised.

Poppa soon took us all up to the mountain, like he had promised. We left by way of the unfenced back meadow. Under a cloud cover that spanned the farm, we strode through an open field. Poppa and Job and I were in front, with Poppa on Job leading me beside them. Molly and Izzy brought up the tail.

As we entered the woods, a towhee called out, so I whinnied hello. Molly called back to me, and even Job whinnied along.

“Well, all right, then,” said Poppa. “Everyone accounted for? Off we go!” he said.

While Job did the work of guiding our party all through the forest, Poppa sat high in his saddle. He looked around at the sky and deep into the trees, and he sang to us of birds and flowers.

“Yellow warbler!” Poppa cried, and then a whir of wings and song flew past. “Just passing through, heading south, I imagine,” Poppa said over his shoulder to Izzy.

Job was on duty so he mostly kept quiet but offered advice, now and again. “Mind your step,” he warned. “Lots of holes and rocks.”

“Job? Will we go to the top?” I asked.

Macadoo of the Maury River

Macadoo of the Maury River Dante of the Maury River

Dante of the Maury River Come August, Come Freedom

Come August, Come Freedom Chancey of the Maury River

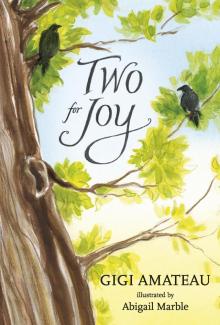

Chancey of the Maury River Two for Joy

Two for Joy