- Home

- Gigi Amateau

Macadoo of the Maury River Page 9

Macadoo of the Maury River Read online

Page 9

“I really get to ride in my socks?” Naomi asked.

“Yes. Now, relax and breathe. Seated like that, facing forward and sitting up with both hands on the surcingle bars, is your basic seat in vaulting. It’s called astride. Everything you learn will build from here. Eyes forward; ears on me. Raise your arms up alongside your ears. Palms out. I’ll control Mac.”

Like always in vaulting, Mrs. Maiden and I formed the course ourselves by creating a small working circle inside the big riding ring. Mrs. Maiden stood in the center, using a whip and a longe line to direct the pace at which I traced the circle. I only stopped moving at Mrs. Maiden’s request or if my rider lost balance, and even then, sometimes, Mrs. Maiden would crack the whip near my hindquarters to remind me to keep going.

Naomi started out at the walk. She lifted her arms straight out from her shoulders out to her sides.

“Are those your ears?” Mrs. Maiden asked.

The girl giggled.

Mrs. Maiden giggled, too. “Now, try to relax and feel Mac’s walk.”

Over the weeks, during our lessons, I kept one ear always on Mrs. Maiden and one ear always on Naomi, who took to vaulting like the Canada geese had taken to chasing me through my old paddock.

If Naomi turned to watch Mrs. Maiden explain something new, Mrs. Maiden corrected her. “Why are you looking at me? Listen and look ahead, always ahead. And point those toes; pretend like you’re a ballerina up there, Naomi.”

Week after week, we improved. As the days turned dark and short, my winter coat grew as long and thick as ever, and Naomi’s vaulting lessons moved indoors. She wore wool gloves, a down coat, and a grin on her face that I could feel even in the touch of her hands.

Naomi learned to move fluidly with all of her body, using all of mine for support. Her hands strong on the surcingle and her feet pressed into my dock made a push-up, a nice warm-up position to remind Naomi that she would need all her length and her strength. One leg extended long along my crest, a bent knee resting on my croup, and arms reaching head to tail were her favorite position — advanced move called special K.

For an hour each week, Naomi learned and practiced her compulsory moves, a basic set of positions that every vaulter must master, link together, and perform in order.

Scissors was the hardest for me and for the rider. In this trick, Naomi would press her weight into the surcingle handles, then swing herself into the air, crisscross her legs, and twist her body to land facing my tail. It took lots of hard landings for Naomi to develop enough strength to make the move look graceful and to soften her landings on my back.

By springtime, Naomi moved from trick to trick smoothly and with ease. Naomi and I had shed our coats — much of mine was shed on her and my other students as they groomed me — and she was vaulting all her movements at a trot, and trying some at the canter. Now Naomi wore her own special shoes with grips on the soles, made just for vaulting — a gift from her foster mother.

At last, Mrs. Maiden told her, “You’re ready to stand.”

During our lesson one morning, Naomi’s foster mother came out especially to watch us. Like always, Naomi curried and brushed me before our lesson. I was sorry that I had gotten so dirty on a day when we had an audience to impress, but the girl didn’t seem to mind. She was thinking about our routine.

“I warmed up on the barrel, Macadoo. I’m ready. Are you?” she asked me.

I am ready. I told her with my stillness. I am ready.

A high-noon sun and a daylight moon framed the riding ring, giving Saddle Mountain clarity and brilliance. The mountain gave me confidence. I relied on Saddle Mountain to be there for me every day; it told me I was home. Naomi could rely on me that way. I imagined myself wide and broad, gentle and strong like a mountain in this child’s service.

Mrs. Maiden clipped the longe line to me, and with a flick of the whip in the air, I started to trot. Naomi ran along beside me, grabbed hold of the surcingle, and mounted on her own. She moved silently from basic seat to flag to mill. She sat for four beats, then swung up into scissors and landed backward so softly that I didn’t wobble or jerk my head at all. The scissors return done in reverse brought her back to sitting astride. From there, she hopped up onto her shins, then to her feet, and then Naomi pressed up to standing. She raised her arms high and stood tall on my back.

For ten strides, she balanced on my back, high up off the ground while I trotted a circle. She drew upon all of the strength in her legs and her torso and her back. With her back straight and her chin up and a slight bend in her knees, she shone.

“Ready to show off your special dismount?” Mrs. Maiden asked her.

She prepared for the last move, a flank: starting with a handstand into side seat, with both legs on the inside.

From side seat, Naomi returned to sitting astride, leaned backward, lifted her legs, and somersaulted off of my back. She landed firmly, confidently, on her feet. I halted beside her and nickered.

Naomi wasn’t afraid of me anymore. She had used my size and my power to help her become a star. She even became the captain of the vaulting team after Ashley started leasing Dante. And, when the day came that she left the Maury River Stables, finally to return to her first home, she was a stronger girl.

“Thank you,” she whispered to me that day. “I never thought I could ride a horse without being afraid, but I can. I love you, Mac.”

My strength had helped Naomi find hers.

I wouldn’t say I forgot Izzy, not at all. I was surrounded by nature and creatures that Izzy loved and that he had taught me to love, too. In daytime, I noticed birds that Izzy had first shown me — the tiny phoebe, who called out her name, “Phee-bee! Phee-bee!” At nighttime, surrounded by moon and sky and stars, I could always make out Pegasus. And, I saw that Izzy was right: Mira Stella left the night sky for a very long time. I searched the sky for her every evening until the sun rose. And then I went to work, again.

I started training for a new job at The Maury River Stables, too. Mrs. Maiden told me that I could work in the therapeutic riding school.

“I had to test you a bit first,” Mrs. Maiden said. “In the therapeutic program, your special job will be to accept each student for who they are and what they present to the lesson. You’ll learn to sense even the smallest hopes that each student brings to our barn and learn how to make those hopes grow even brighter.”

My friend, Gwen, also worked in the therapeutic school.

“Mrs. Maiden says you change people’s lives in the therapeutic school. Is that true?” I asked Gwen one day at our regular meeting place, the high corner where the mare and gelding fields joined.

She flicked me with her tail. “The therapeutic school isn’t that different from the lessons you teach now. Sometimes, we even teach vaulting in the therapeutic program. We always attend to whoever sits in the saddle, whatever their needs are. Besides, all horses changes lives, Macadoo.”

“By working hard?”

“Partly.”

“How else?”

The Hanoverian reached out to me. “Leave yesterday behind. Today you are here, Macadoo. Let today be your joy and you will bring joy to all those you serve.”

Mrs. Maiden’s barn manager, a gentle man named Stu, prepared me for the therapeutic school. He showed me shiny objects; he rolled twine across my shoulders and withers — all to teach me still and quiet manners.

Stu took me on solitary rides around Saddle Mountain to get me used to the unpredictable world around me, but I already knew all the sights and sounds of the mountains. Stu and Mrs. Maiden didn’t understand: I had grown up with the splendid mountains. With Izzy. And Poppa, Molly, and Job. My training for the therapeutic school had started all the way back at Cedarmont.

The mountain was like a good and true friend, and Stu found that I could not be spooked on or off the old logging trails. Those roads, cleared long ago by drafts like me, made for an easy path, and nothing scared me. I walked right up to the wild turkey; I trotted over the

fallen pines. The Maury River refreshed me on this side of the mountain, too. Off trail, I knew how to step down and up the steep rocks. I never bolted once.

I proved to be a steady and sure worker. In the springtime, Stu told Mrs. Maiden, “If I didn’t know he was a hundred percent Belgian, I’d swear to you he had some mule in him. He’s ready.”

On my first day working in the therapeutic school, Mrs. Maiden strode into our field with my halter slung over her shoulder. “Mac, come on.”

I walked over, ready to work.

“I believe you’re finally getting used to me. It’s about time.” Mrs. Maiden reached up and placed my halter over my earsand buckled it around my cheek. She tacked me up for my first student and Stu led me to the ring, where a child waited at the chair ramp.

As a colt, when I was so scared to leave Mamere, the sound of one boy’s voice had given me hope. But at the Maury River Stables, there were nice ladies, like Mrs. Maiden, and nice men, like Stu, and so many girls, but I had about lost hope of ever hearing a boy say my name again, when I heard a young boy’s voice call me.

“Macadoo! I’m up here!” Eric Sand said. “Look at me!” He sat in his chair on wheels, waiting at the top of the ramp. Izzy might not ever come, but this new boy needed me to be his horse right then, so when he waved at me I nickered back.

“Yeah, Mac!” He pushed his feet down into his chair and leaned back his head. “Ha, ha! He likes me,” Eric said to his mother.

Mrs. Maiden stood on the ramp with Eric. Stu guided me even with the ledge and held me straight. I kept still and quiet, just as I had been taught while Mrs. Maiden eased Eric onto my back and into a specially made saddle for two people.

Eric’s mother looked around like something was lost. “My husband, Virgil, should be here any minute to help,” she explained. “He’ll come; he promised.”

“Yeah,” said Eric. “My dad’s coming.”

An old, dented truck turned down the drive and parked on the grass instead of the gravel.

“Sorry, I’m late,” said Eric’s father. He reached out to pat me, his hand rougher than Poppa’s, less sure than Stu’s, and when I gave him my breath, he pulled back.

Then he breathed a long sigh and looked to Mrs. Maiden. “Should we get started?”

Mrs. Maiden nodded. She told the Sands, “As I understand, you’re here because Eric wants to learn to ride. We can do that, but we’re going to take it pretty slow. Does that sound fine with you?”

Eric tossed his head back and raised his hand high in the air.

“Thatmeans yes,” said Virgil Sand.

Mrs. Maiden smiled. “I picked that up. Eric you look happy sitting up there on Mac. I’m so happy your mom called me. I believe that anyone can learn to ride. Did you ever think you’d get to ride a big horse like this?”

As Mrs. Maiden explained our work, she spoke to Eric directly. “The reason we’re going to take our time is because with brain injuries, we want to be sure that we give you and Mac whatever you need together to become a good team. There’s a lot to consider — balance, alignment, and how much rest you might need. I want you to be safe and have fun. So, are you ready?”

Eric clapped his hands. “Ready!”

On our first day, Eric sat in that saddle made for two with his father. Mrs. Maiden stood at my head. Stu stood to one side of me; and Eric’s mother on the other. Virgil sat behind him with his arms around Eric’s waist. I carried them both in the curve of my back. With the strength of my two thousand pounds, I held father and son.

While I walked, I could see the geldings racing one another to the top of the field and back again. I could not run and did not want to, for I was working.

After Eric’s first lesson, he waited at the fence line with his father for Stu to turn me out. Stu brought me over to say good-bye first. Eric stayed in his chair, across the fence and near enough to touch my coat. He held his hand out with an apple. I lowered my head and took half of it.

Eric laughed and said, “Again!”

I took the other half and felt one of his fingers in my mouth, too. I didn’t bite him, but Erick shrieked.

I tried to nuzzle him an apology through the fence, but heard his father say. “Get away from my boy.”

“The horse didn’t hurt him, Virgil,” said Eric’s mother, Amy.

“Yeaaah,” Eric called out.

I nickered at the boy. He waved his arm to me.

“That horse is supposed to help Eric not scare him. That’s its job.”

His wife said softly, “Did you see Eric laughing? Tell me the last time anything or anybody made Eric laugh.” She reached out for her husband’s hand. “I’m happy we came here. I love my boy. He’s a good boy. I love you. You’re a good man. I think this is a good horse. Don’t be angry, okay?”

Then Amy Sand gave Virgil a carrot, and he held it out to me. I moved toward him and was careful with my teeth.

Eric swung his head and arm toward me. “Good boy, Mac. Yeah, yeah.”

Eric Sand and I worked together on Saturdays, and there were more therapeutic lessons on Tuesdays and Fridays with Sam and Amelia. The vaulting team practiced with me on Thursdays and Sundays. And, I had lessons with the ladies on Wednesdays because very few of the students’ mothers could resist the riding ring. Even Mrs. Pickett who kept a donkey across the road, started taking riding lessons. Though Mira Stella did not return for night after night, every day my students did.

The autumn after Naomi left, I met Claire. A child, smaller than any I had ever met, appeared in the gelding field one crisp Saturday morning. Napoleon, the fat Shetland pony, was too busy eating hay to notice. Dante, our black Thoroughbred leader, couldn’t waste his time on a child when the other geldings — Charlie, Cowboy, Jake, and a new boarder, George — needed rounding up. So, I went to see about her myself. I found her standing by a fence post, talking with sparrows.

Neither Mrs. Maiden nor Stu seemed to have brought the girl to the field. Wearing old, torn overalls and new paddock boots, she stood grinning at me in the tall grass. I remember that her top front teeth were missing then.

“I’m Claire! I’m eight!” she said. “Mrs. Maiden says I get to take my first lesson on Daisy. I would rather ride you. I’ve read about your breed at the library. You’re a Belgian. I love Belgians!”

I had only met one other child, Izzy, who wasn’t afraid of me at first because of my size. Claire wanted to feed me by hand. She reached through my fence to a spot beyond my reach. Claire held her palm open and offered me a clump of wet grass.

Carefully, I took it from her — so much sweeter than the overgrazed offerings inside our field.

“You are a gentle giant.” She recited this as if it were a fact.

And while I sniffed around for stray clover, Claire told me more about Belgians than I ever expected a child to know.

“A long, long time ago, like, hundreds of years ago, your ancestors were famous. The Great Horse of Flanders, Macadoo, that’s you! Knights rode you into battle. Farmers harnessed you to till the soil. That’s what the book said, ‘till the soil.’ I guess Belgians were tractors before there were tractors.”

Claire squatted down in the grass beside me. She reached her hand out toward my cannon and fluffed the long hairs growing there. “Nice horse feathers! Your winter coat is thick already. Kinda muddy, though.”

Such a tiny little person, yet she showed no fear at all. I thought she might be settling in for a good long story about my breed, but the gate swung open and Mrs. Maiden came running into the pasture. Claire hopped up fast and tried to hide away behind me. “Uh-oh,” she said.

“Claire!” Mrs. Maiden yelled. “Why did you run off? From now on, you only come out here with an adult — at least until you’re older and more experienced. Do you understand?” Mrs. Maiden took a deep breath.

Claire looked at the ground. “I’m sorry, Mrs. Maiden. I’m sorry, Mom.”

A grown-up who looked a lot like Claire stroked the girl’s hair. “I ask

ed you to wait with the older girls while I was in the office with Mrs. Maiden.”

“But, I saw the Belgian, just like in the book we read, remember? I wanted to meet him,” Claire tried to explain.

The woman took Claire’s hand and started toward the barn. I followed behind them.

“So, you know a lot about horses, Claire?” Mrs. Maiden asked. “Let’s see how well you know your breeds. I said you’d be riding Daisy this morning, right? She’s a gray Welsh cob. Find Daisy for me.”

Claire nodded. She looked to the mare field where Gwen and her mares grazed just across the fence line. “There! There’s a Welsh cob — a flea-bitten gray. And look beside her, a Hanoverian! She’s so beautiful, a blood bay, and she has three socks.”

Mrs. Maiden laughed at how smart Claire was about horses. “That’s right! The Welsh is Daisy; Gwen is the Hanoverian. Now, let’s see. Napoleon is a Shetland pony. Find Napoleon for me now.”

Claire giggled and pointed to Napoleon’s rear end, sticking out from behind the hay ring. “That’s easy!” she said. “There’s the Shetland! He’s a red roan.”

“Really? You even know that?”

She was showing off then. “Yep! Red roan means a reddish coat that’s sort of frosty white on top. Oh, but, Mrs. Maiden, I didn’t know a Belgian lives here. Could I please ride him today?”

“No, not yet. He’s a little big for you. Say good-bye to your friend, Macadoo. Let’s go tack up Daisy. I’m sure you’ll be riding Mac in no time.”

I followed Claire to the gate and whinnied for her to return soon, which she did with lots of treats! Mrs. Maiden was right. By winter, Claire joined me for a weekly vaulting lesson. By spring, she was proficient in most of the basic vaulting positions. Flank gave her more trouble than standing. By summer, she could even perform a special K — hands free of the surcingle at a trot. That summer, after Claire turned nine, she signed up for a week of riding camp. Mrs. Maiden let each child care for one horse during the entire week. Claire chose me.

Macadoo of the Maury River

Macadoo of the Maury River Dante of the Maury River

Dante of the Maury River Come August, Come Freedom

Come August, Come Freedom Chancey of the Maury River

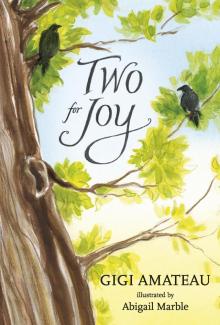

Chancey of the Maury River Two for Joy

Two for Joy